University has stripped me of my faith in religion, state and flag, and the inevitable process of growing up has pulled the wool from my eyes in terms of parents, school and relationships. If there is one thing I revere, however… one person I understand as

Immortal… it would have to be Charles Spencer Chaplin. Chaplin, the endurable deity of the Cinema Temple and the Silver Screen. The man who proves that one does not have to be infallible to be an idol.

I say all this not to attempt to convince you to worship the man as I do, but merely to counteract any charges that I am biased in this review. There is no need to charge me thus. I am perfectly well aware of my bias.

That is why it has taken me this long to broach the topic of Chaplin. I feel no desire constantly to lay out positive, gushing reviews, time after time, so it took some doing to pick a Chaplin a film to cover.

City Lights (1931), his most perfect film in my view, for example, needs no review. It is a classic, akin to Scripture. What kind of article would that make?

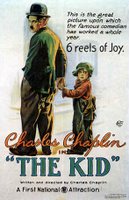

Therefore, I have hit on the silent film

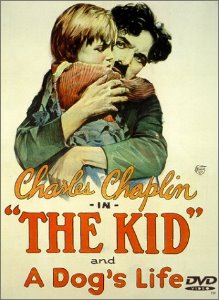

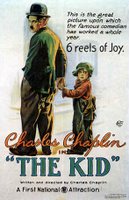

The Kid (1921), Chaplin’s first feature film involving the Tramp. This film is certainly a classic, but it is a

flawed classic. This state is what makes it a perfect subject for a review.

The Kid was inspired by the loss of Chaplin’s first son, Norman Spencer, in infancy. His marriage to Mildred Harris, his first child bride, was failing, and he was entering a depressive state, both mentally and professionally, and was under the weight of a massive block. Then, by chance, Chaplin happened to see a stage show that featured a bizarre and precocious little child dancer by the name of Jackie Coogan, and, realizing this boy was the answer to his prayers for a muse, a deal was struck and a picture developed.

The result was “six reels of joy,” the picture “with a smile, and perhaps a tear.” The picture starts out with a poor and abandoned unwed mother who is coldly dumped from her charity hospital refuge with her newborn son. Despondent, she leaves the child in a limousine and heads off to commit suicide; however, she cannot kill herself and she returns to collect her son. Finding that the car has been stolen, she is struck with guilt and horror, for her child is now irrevocably lost to her.

Enter the Tramp.

Enter the Tramp. Taking his morning constitutional, the funny little man in the strangely pompous and deplorable suit, and with the even odder walk, comes down his skid-row alley with the nonchalance of a duke in Bath. Opening an old sardine tin, he carefully selects the best of his salvaged cigarette butts, and lights up. He is the very image of all that is poor and meager, as well as all that echoes the Victorian ideal of gentlemanly leisure.

Finally, a noise catches his attention. The baby, discarded by the crooks who stole the limousine, lies next to a dust bin. After some very desperate attempts to ditch the burden, the Tramp finds the note: “

Please love and care for this orphan child.” That is all it takes, for the Tramp always falls in love with anything as defenseless and pitiful as himself. (See for example, the marvelous

A Dog’s Life (1918), one of Chaplin’s best shorts.)

Five years pass. The Tramp, despite his slum apartment (which was clearly torn from Chaplin’s own childhood memories of the impoverished lanes of East London), he has become a caring and responsible guardian for the boy. Jack, a beautiful and utterly charming tow-headed angel/devil, returns the care back to his small and powerless father. Their domestic bliss is palatable and wonderful, and our hearts glow when we see the chemistry between them.

Soon, of course, the boy gets sick and the county steps in, leading to that magnificent and iconic scene of the Tramp fighting to keep his son in the face of bureaucratic brutality. Small and weak, the Tramp nonetheless slays demons (or at least knocks flat a cop and a social worker), scales the roof tops, leaps to a speeding truck, and saves his son from a horrible and bleak life as a poor-house orphan. Truly, there can be nothing more wrenching as, without dialog, we see the pleading boy cry over and over again, “Oh, I want my daddy!

Please! I want my daddy!” And there is no greater crescendo in film history than the moment that the two are reunited.

This scene – the triumph of the common man against state interference and cruelty – is, by rights, the heart, soul and guts of this picture, and, even after nearly ninety years, it has barely lost an ounce of its power. The major error in this film is that this is not the last impression of

The Kid.

After the Tramp saves the boy, and they are cast into the streets as runaways from the Law (and we find out that the boy’s mother is now rich and seeking out her child after finding the note in her own handwriting in the Tramp’s flat), the boy is stolen by a reward hunter. Despairing and alone, the Tramp haunts the city searching for his lost child. Finally, all hope lost, he sits on his former stoop and falls into a deep sleep. What ensues may be one of the clumsiest and disturbing dream sequence debacles ever to mar an otherwise magical film.

Chaplin was a romantic, and his artistic impulses were always passionate, but not always technically correct, and

The Kid fell prey to a flight of fancy.

The fact that he dreams of an egalitarian and peaceful paradise in which all the inhabitants (even the authorities) live in harmony, and where food is free and love is all around, does not shock in a Chaplin film. Frankly, given the talent for dance and whimsy that Chaplin possessed, this sequence might not even have been all that bad on its own. Rather, it is the deeper significance of the dream sequence in

The Kid that repels and disappoints.

In this dream, which only barely connects with the rest of the film, the Tramp (and his alter ego, Chaplin) lives in perfect peace and innocence. Then “sin creeps in.”

This sin comes in the form of a 12-year-old actress, played by none other than the woman soon to be known as Lita Grey Chaplin.

At 12, her beauty had so interested him that

The Kid’s blemish was created just for her, and the result is a psycho-analytic nightmare, and an all-too-insightful vision of the future. The girl, tempted by Satan, lures and entraps the Tramp (Chaplin), causing his life to be ruined in the form of legal troubles and exile. Given the consequences of Chaplin’s later disastrous marriage to the 16-year-old Lita, this dream sequence plays now as one of the most bizarre (and uncomfortable) auteur shows-of-hand ever filmed, with the possible exception of Woody Allen’s otherwise wonderful

Manhattan (1979).

I have seen

The Kid at least 50 times, including twice on the big screen, and it is always a joy to introduce new people to its emotional highs and lows, and to hear whole new audiences laugh uproariously at the clever comedy bits. However, every time I see it, amidst the delight, I must give a small cringe at this dream sequence, and every time I am reminded that hubris and flaws, even in an artist I admire so much, must sometimes come out.

However, it remains as a reminder, too, that the romantic enthusiasm and idealism that so disfigured

The Kid also created the moving

plea for sanity at the end of his first talkie, the anti-Nazi film

The Great Dictator (1940), and I am reconciled.

Once upon a time, one did not have to specify who Chaplin was. He was a force, like Pan or Eros. Chaplin was the king of all he surveyed. And he got that way by following his instincts.

No one thing is perfect. Flaws make a film, as much as does the beauty.

The Kid, despite its impassioned and discomforting error in judgement, is as deeply beautiful as it is deeply flawed. It is a picture with both laughs and tears, and a great deal of humanity that resonates now and will most likely never fail to charm an audience of any era.